The Teen Who Won an Audience With Lincoln

At age 17, Vinnie Ream was a talented young woman pursuing her dreams. She had grown up on the frontier in Wisconsin and attended school in Missouri where she showed artistic talent. In 1861, her family moved to Washington, DC for her father to find work. As her father’s health declined, Vinnie sought work with the U.S. Post Service in the Dead Letter Office. The nation was in the midst of the Civil War, and jobs traditionally held by men were suddenly opened up to women, at least temporarily.

But Vinnie’s path didn’t end at a clerk’s desk. Her lower middle class family made connections with congressmen, and one of them recognized Vinnie’s artistic gift. He arranged for her to study with a well-known sculptor, Clark Mills.

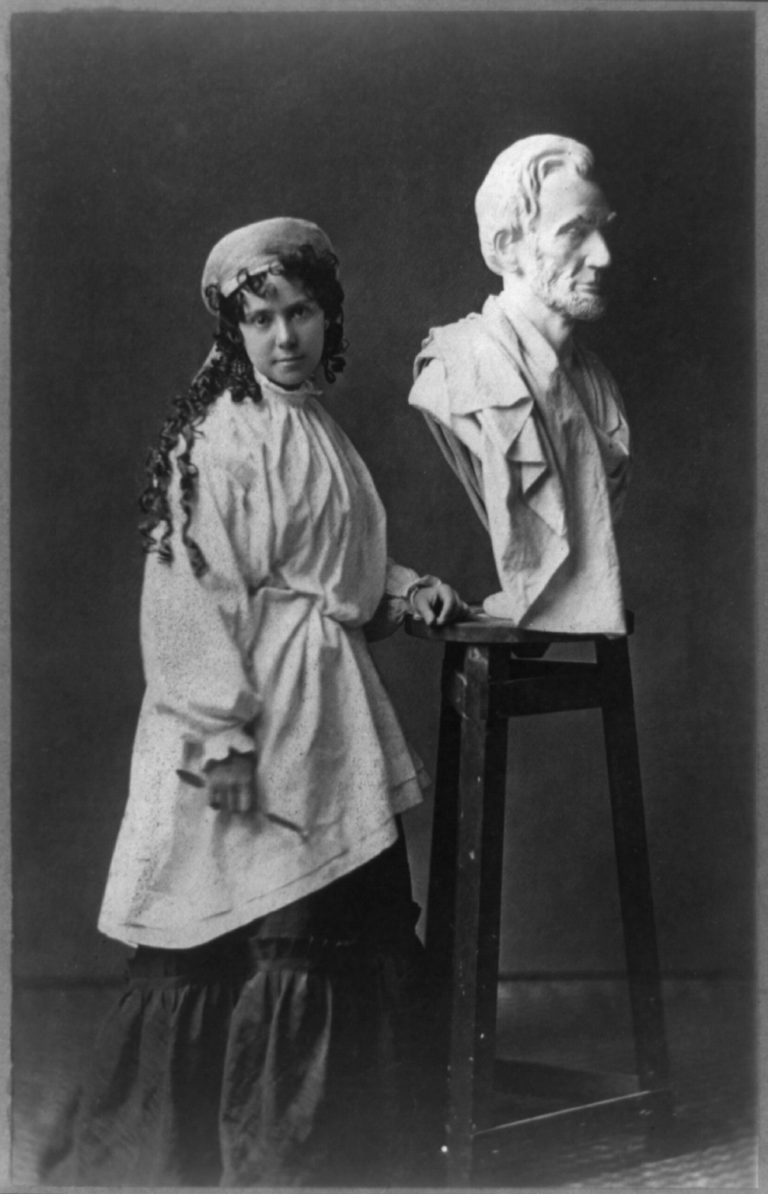

Vinnie’s miniature likenesses of General Armstrong Custer, Senator Thaddeus Stevens, and several congressmen garnered her attention. At age 17, only a year after she’d begun her study with Mills, Vinnie was commissioned by a group of senators to create a marble bust, and they allowed her to choose the subject. She selected the man she greatly admired, the president of the United States.

In 1864, Lincoln was knee-deep in body counts and praying that his new commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant, would be able to galvanize the north to victory. Too often petitioners lined the hallways and stairways of the White House seeking a few minutes or an hour of Lincoln’s attention. He didn’t have time to sit for a sculptress, and he initially refused.

However, he changed his mind once he discovered Vinnie Ream was a poor girl who’d grown up on the western frontier. Vinnie later wrote, “He granted me sittings for no other reason than that I was in need. Had I been the greatest sculptor in the world I am quite sure I would have been refused.”

So the teen received a half hour a day for five months with the president. According to Vinnie, the president seemed to use it as a time to relax away from the barrage of responsibilities.

She treasured her time with him and grieved his death several months later: “So lately had I seen and known President Lincoln, that I was still under the spell of his kind eyes and genial presence when the terrible blow of his assassination came and shook the civilized world. The terror, the horror, that fell upon the whole community has never been equaled.”

In the nation’s hour of grief, Congress decided to commission a full-size statue of Lincoln as a memorial to the fallen president. Eighteen sculptors vied for the honor, including Vinnie’s former mentor Clark Mills. Vinnie, adept at marketing and networking, campaigned to be selected. She won. Her irate detractors declared that she was too young, and a woman besides. One senator exclaimed, “I shall expect a complete failure in the execution of this work.”

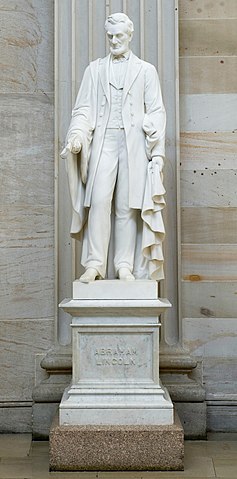

Four and a half years later, in 1871, Vinnie’s rendition of Lincoln was unveiled in the Capitol rotunda, a realistic portrayal of the man in an era when most sculptors sought to create idealized, larger than life versions of their subjects. Lincoln stands there still on the sandstone and marble floor with the Emancipation Proclamation in his hand.

In the years following, Vinnie set up her own studio in Washington and received a commission, beating out twenty-four competitors, to sculpt Admiral Farragut, the famous naval Civil War heroe.

However, in her years of completing the work, she met Lieutenant Richard Hoxie, a friend of Farragut’s son. She fell in love and married him in 1878. A man of his times, Hoxie believed his wife should focus on their home and family-to-be. Vinnie complied, and for the next couple of decades, her artistic efforts were few and far between.

I can’t help but wonder what it would have been like for her to give her pursuit of her dream for this man. She loved him wanted to spend the her life with him. But to set aside the clay, the bronze, and the marble for decades?

She and Richard had a child. I’m sure she loved the boy and wanted to devote herself to her family. Yet her hands and her heart must have yearned to put her gift into action once more.

Years later, Hoxie relented, and Vinnie vied for a commission. She won the opportunity to sculpt Samuel Kirkwood, the governor of Iowa during the Civil War. After that, she created a statue of Chief Sequoya, the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary. Vinnie passed away as she was finishing the sculpture. Both of her last two statues stand in the National Statutory Hall at the Capitol.

She was a woman of great talent who used her spunk and determination to win opportunities for pursuing her dreams. Then, she set her work aside for decades for the man she loved.

I’m thankful that I don’t have to make such a choice. I’m thankful for a husband who supports me the pursuit of my writing dreams and calling.

Sources:

Conradt, Stacy. “Vinnie Ream: The Teen Who Met With Abraham Lincoln Thirty Minutes Every Day.” Mental Floss. 11 Feb. 2019. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/83640/teen-who-met-lincoln-30-minutes-every-day

Echsner, Kate. “This Ambitious Young Sculptor Gave Us a Lincoln for the Capital.” Smithsonian Magazine. 25 Sept. 15. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ambitious-young-sculptor-gave-us-lincoln-capitol-180964974/

The Congress of Women Vol. II: Held in the Women’s Building, World Columbian Exposition. 1893.

“Vinnie Ream.” Architect of the Capital. https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/vinnie-ream

6 thoughts on “The Teen Who Sculptured Lincoln”

Wow, quite a woman Vinnie was!!! Sometimes I think because the population was far less than now, it was easier to spot talent/become known. But maybe talent is talent wherever, whenever. Anywho, thanks for this interesting story!!! 🙂

From what I read, I believe she was quite a go-getter. I believe she used her charm and determination, along with her parents’ networking skills in order to open the doors of opportunity. She was also good at convincing others that she was the right person for the job. When it came to the full-size Lincoln statue, she had to campaign against 24 other artists. Later, when she earned the commission for the Farragut statue, it was because she convinced Farragut’s widow and General William Sherman that she was the best person for the job. I feel that as writer’s we could learn a thing or two from her when it comes to marketing:)

Loved reading this. I had never heard of her.

I hadn’t heard of it either until last month. I thought it was really cool that a teen-age girl back in the 19th century when the vast majority of women stayed at home was able to sculptor the president of the United States.

Wow, what a great story of what a woman did way back when.:)

I’m amazed at how much she accomplished as a 19th-century woman. Thanks for stopping by, Kathy:)

Comments are closed.