Moravians Amongst the Cherokee: Cultural Barriers Overshadowed by Love

By Sarah Hanks

In co-writing A Silver Promise, I delved into researching the Moravian missionaries who worked among the Cherokee in Georgia and Oklahoma. Their history and stories sucked me in, bringing up complex questions regarding what success in missions across cultures looks like.

The Moravian Missionaries founded a church and a boarding school among the Cherokee people first in Georgia. Springplace, as it was called, was founded in 1801 and remained for three decades, until the Cherokees were forced west on the Trail of Tears. Several missionaries went with the Native Americans when they were forcibly removed. These Moravians founded New Springplace Mission in September of 1842 in Oklahoma. Tayanita from A Silver Promise ends up at this mission after escaping from the Comanche.

Twenty-one students attended the boarding school at New Springplace where Brother Gilbert Bishop, and later James Ward, taught them reading, writing, spelling, arithmetic, history, and U.S. geography. Many Cherokee parents sent their children to school because of the educational opportunity, not because they adhered to the Moravian’s religious or cultural views. The school faced the ongoing dilemma of parents taking students home for extended periods of time. When students returned, they had forgotten much of their previous learning, causing instructors to spend much of their time reteaching. The solution, of course, was to demand that parents leave their children at school except for the appointed breaks. In practice, however, the missionaries feared upsetting and alienating parents. They never could strictly enforce their attendance rules.

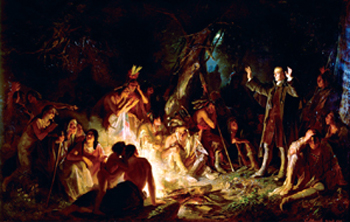

Moravian missionaries also faced a language barrier when ministering to the Cherokee. Sometimes they had interpreters, but other times they would hold entire church services in German. Though the Cherokees couldn’t understand what was being preached, Spingplace in Georgia boasted a congregation of forty-five, including fifteen baptized Cherokee converts and twenty-three children. It was said that “Clear signs of the Holy Spirit’s work of grace” were evident during services and that during many services those in attendance lamented their wretchedness as sinners with tears before proclaiming faith in Jesus. When the Moravians baptized the Cherokee, they gave them new names stripped of their ethnic identity such as Sophina Carolina, Lydia Elizabeth, and Margaret Mary.

Language was not the only cultural barrier the Moravians encountered. Their diaries state that Cherokee children were typically shy and could be frightened by a bold manner of speaking. When communicating with their pupils’ families, their diaries also advise they had learned that a direct manner of speaking didn’t work well to either get their point across or foster good relationships.

For the New Springplace Mission, James Ward and his wife Esther were a godsend. Both were of Cherokee descent and thus knew the language and culture well. James was a Methodist and Esther a Presbyterian, but in April of 1858 they joined to Moravian church when their churches divided over the issue of slavery, and their mission work was hampered. Soon after joining, they moved to New Spingplace where James became the assistant missionary and teacher. He was known to be affable and friendly.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, guerilla bands fought throughout Oklahoma making the area a dangerous place to stay. James’ father had owned a Southern plantation, but James himself was neutral in the war. The Moravian Church was opposed to slavery as an institution and took a stand of neutrality. Despite the conflict, James decided to stay at the mission as a symbol of peace. However, on September 2, 1862, a marauding band of “Pin Indians” (fellow Cherokees who fought for the side of the Union) murdered Ward and sent his family fleeing to the woods. This event resulted in the closure of New Springplace Mission for some time.

In reading through the diaries of these missionaries, I was struck by how difficult the work before them was and how little they had to show for years of laboring among a people they came to love. Decades of toil resulted in small congregations and much back-and-forth. Was it worth it? Could this laying down of their lives be labeled as successful?

While we might look back on some of their methods now through our modern lens and find fault, from their journal entries their deep love for the Cherokee people was evident. The missionaries gave up much to walk barefoot and in tattered clothing among those whose customers were far different from those they’d known. They wept over them and with them. They rejoiced in their salvation and in the prosperity of their communities. Their hearts became intertwined. Though their execution may have been far from perfect, I believe any labor done in love is never in vain.

To read about Tayanita’s experience with the Moravians, check out the short story Sherry and I co-authored A Silver Promise. At the end are recommended resources if you’d like to learn more about the Moravians.

A Silver Promise leads into my novel Fall Back and Find Me where you find out where Tayanita’s silver spoon ends up and what it means to the person who finds it. I hope you enjoy.

Two resilient women separated by over 150 years are linked forever by their challenges, values, and determination.

Amber Prichard is thriving in her role as pastor’s wife, mom, and indispensable church volunteer—until chronic illness threatens to upend everything. Now unable to prove her value, she is forced to reevaluate how she defines herself. Inspired by an ancestor’s faded journal and heirlooms, she must work with her arch-nemesis if she wants to accomplish what is now impossible on her own.

Faced with the turmoil of the civil war, Willow Forrester didn’t intend to illegally enlist in the Union army as a secret female soldier. She only wanted to escape her father’s tyranny and follow her brother into the throes of adventure. When she comes face to face with the leader of a guerilla army, her health and insecurities threaten to shatter her heroism and render her powerless.

As their opposition threatens to overtake them, these two women must find their strength and identity to defeat impossible odds. Amazon

Bio: Sarah Hanks is an award-winning author of Christian fiction in both the contemporary and historical genres. After spending over a decade mostly writing and teaching Sunday school curricula for churches in her community, she finally jumped into writing fiction full-time. She and her husband have nine children of their own, a couple of whom seem to have inherited their mother’s love for playing with words and crafting stories. Though Sarah dreams of a cabin by the beach, the family lives jammed together in beautiful chaos near St. Louis, Missouri. She buys earplugs in bulk.

2 thoughts on “Moravians: Missionaries to the Cherokee”

Interesting article about the sacrifices made to spread the gospel. Thank you for sharing, Sarah!

I was impressed that they even went on the Trail of Tears with the Cherokee. Thank you for stopping by, Patti:)

Comments are closed.